Yemen Between Reality and Myth in Abdulkarim Al-Shahari’s Novel (Rafila)

Yemenat

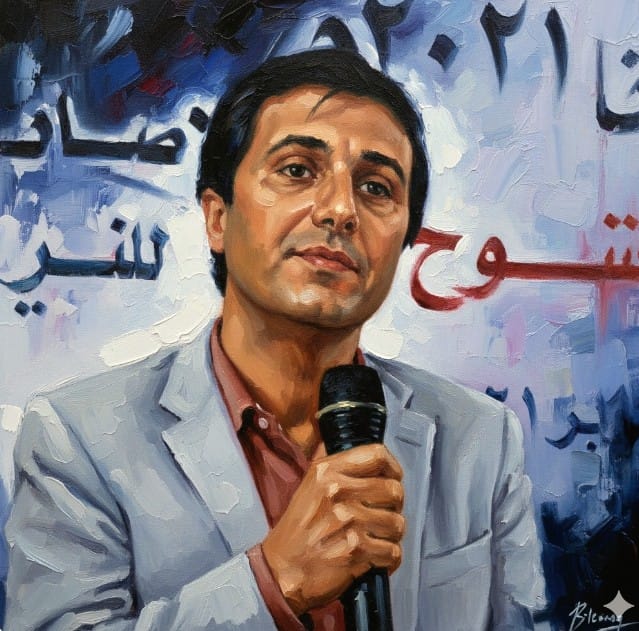

Mohammed Al–Mekhlafi

Abdulkarim Al-Shahari’s novel (Rafila) registered at Dar Al Kotob, Sana’a No. 480 of 2023) attempts to navigate the intricate complexities of Yemeni reality. The narrative unfolds through five distinct threads, some overtly political and others veiled in mystery and myth.

This review seeks to deconstruct the relationship between fact and folklore in the novel, exploring how Al-Shahari employs both to examine why the national project in Yemen has so often faltered.

When I first saw the title Rafila printed in bold on the cover, I expected a romance. However, the full title (A Light That Never Saw the Sun (1).. Rafila.. A Tale of Two Revolutions) left me puzzled. As I continued reading, it became clear that this subtitle is the essential key to the entire work.

In this context, the (Light) represents the recurring dream of a nation reborn time and again, carried on the shoulders of men who believed they could lead the country out of darkness. It symbolizes the brief transformative era of Ebrahim Al-Hamdi, echoed in the characters of Tawfiq, Mohammed Hatem, Mahmoud Zahir, and Alia.

These figures serve as the novel’s conscience, seeking to understand before they judge and to reform before they dominate. Yet, as the title suggests, this light was never meant to shine. It remained confined to closed rooms, strangled before it could reach fruition.

(Rafila), on the other hand, symbolizes Yemen itself. It is a land that captivates rulers, revolutionaries, and even supernatural forces. Each believes they can possess, save, or reshape it, yet in the end it slips through their fingers, leaving them defeated or dead on its pavements.

Its beauty appears inseparable from its tragedy.

As for the (Tale of Two Revolutions), the author suggests that the February 11, 2011 uprising was merely an echo of earlier unfinished revolutions. The first narrative thread opens with three military officers, Ebrahim Al-Hamdi, Ali Abdullah Saleh, and Ahmed Al-Ghashmi, who appear suddenly in a remote oasis on Yemen’s northwestern coast.

Surrounded by papaya and mango trees, the setting feels detached from time, a space where the Yemen we know intersects with the metaphysical myths that have shaped its history.

The scene begins with a bizarre car accident on a February night in 1974, marking the arrival of three witches, Hend, Send, and Fanousa, who become central to the narrative. The dialogue between the officers and these witches exposes the nature of power and the labyrinth of history, forging a direct link between past grievances and contemporary conflicts.

The characters of (Athkul and Barnousa) symbolize the hidden forces that manipulate those in power. This symbolism reaches back to the era of king Al Toba Hassan Al-Yamani, who was advised by his father, As’ad Al-Kamel, never to act without their guidance.The message is clear. Any ruler’s ego, greed, or disregard for these (unseen) forces inevitably leads to tragedy.

This is illustrated when the King attempts to force a marriage with Al-Jalila despite warnings from Athkul and Barnousa, particularly because she was already betrothed to her cousin, Kulayb. His downfall is sealed when Al-Jalila conspires with a witch against him. In this moment, myth and human relationships intertwine, and modern Yemen appears as an extension of that ancient past.

Al-Jalila stands as a symbol of power and human desire. By linking her to the King’s arrogance and lust, the author dissolves the boundaries between time and place. Reality and myth merge seamlessly.

The tension intensifies when the three titans of power meet. Al-Hamdi appears composed, Saleh visibly cunning, and Al-Ghashmi driven more by emotion than intellect. When these men confront the supernatural through the witches and the omens of Athkul and Barnousa, the atmosphere becomes deeply unsettling.

The assassination of Al-Hamdi at the hands of his comrades and Saleh’s decades-long survival reflect cycles of conflict that persist today. The text states, (The mad reign of one of them will endure because it will rely on the support of Athkul and Barnousa) (p. 9). This sentence encapsulates Al-Shahari’s philosophy. Power in Yemen is inherently fragile, regardless of its duration, and ego is the first nail in a ruler’s coffin.

The oasis functions as a liminal space where political authority and the occult converge. History and legend merge into a single image. When Hind declares, (We are Yemeni and this is our identity, but we are not for marriage; we are witches) (p. 11), she reinforces the idea that Yemen cannot be reduced to a single ruler or regime. It is larger than any attempt to confine it.

The meeting of October 10, 2010, south of the capital further illustrates the struggle to control history and the ways in which the past is weaponized to reshape the present. Rafila connects Yemen’s past and present in a direct and unembellished manner, avoiding unnecessary exaggeration.

Despite its scientific façade, the archaeological excavation company in the novel seeks to transform knowledge into power. The treasures, like Athkul and Barnousa, represent Yemen’s historical depth and demonstrate how the past becomes a tool of influence in the hands of those who can decode and exploit it.

The characters reflect the multifaceted Yemeni struggle. Sandra attempts to understand events through logic but collides with hidden forces beyond her control. Januar drifts toward appearances, repeating Yemen’s historical mistakes. Fanousa reminds us that the past is never truly gone but remains an active force shaping the present.

Sheikh Suwar and Tarif bin Jureid demonstrate how authority, religion, and knowledge are manipulated as events unfold. Tawfiq, the intellectual who always arrives too late, embodies the fragility of the individual in a nation that continually reproduces its crises. Al-Shahari compels readers to view Yemen from multiple angles, prioritizing an understanding of conflict over a mere recounting of events.

The symbolism extends beyond Yemen. Rafila is linked to the Yemeni Banu al-Ahmar family, the last dynasty to rule Granada. Through this connection, Al-Shahari bridges Andalusian history and Yemeni reality.

The reference to Mohammad XII of Granada, known as Boabdil, and Isabella I of Castile evokes the fall of Granada not simply as a historical event but as a metaphor for the collapse of national projects when internal divisions intersect with external interference.

By explicitly mentioning Ali Abdullah Saleh, the novel anchors itself in political reality. It reveals how those in power manipulate both history and myth for personal ends. Revolution and its symbols become arenas for a relentless struggle over authority and knowledge. No final victory emerges, only the recognition that the struggle continues.

In its later chapters, the novel offers a direct critique of Yemeni revolutions, exposing how they are emptied of meaning and how principles collapse at the first serious test. By 2014, familiar archetypes appear: the revolutionary turned minister, the intellectual turned victim, and friends divided by power rather than ideology. The central conflict shifts from myth versus reality to conscience versus authority.

Mahmoud Zahir, Tawfiq, and Mohammed Hatem represent a fractured Yemen in which politics becomes a stage for settling personal scores. The novel exposes the state’s cruelty, particularly toward the widows and orphans of martyrs.

Yet Al-Shahari grants even the executioner a human dimension, portraying him not as a monster but as a defeated man who knows the truth and chooses silence to preserve his position.

In its final sections, the novel reveals the face of a police state where intelligence agencies, religious institutions, tribes, and personal interests intertwine. Characters such as Salim and Tarif illustrate how personal vendettas or radicalized knowledge can devastate a nation and how revolutions are engineered behind closed doors long before they reach the streets.

The novel concludes in total collapse. There is no victory and no salvation. Tawfiq’s mysterious death at the hands of fellow revolutionaries signifies not only personal tragedy but the defeat of reason and the disintegration of the national project. Yemen emerges as an unfinished dream, a solitary revolution, and a beautiful country drained by politics, religion, and fear.

Rafila stands firmly within contemporary Yemeni literature. By weaving together myth, history, and politics, Abdulkarim Al-Shahari crafts a complex narrative that compels readers to experience events intimately and to grasp the profound intricacies of the Yemeni struggle.