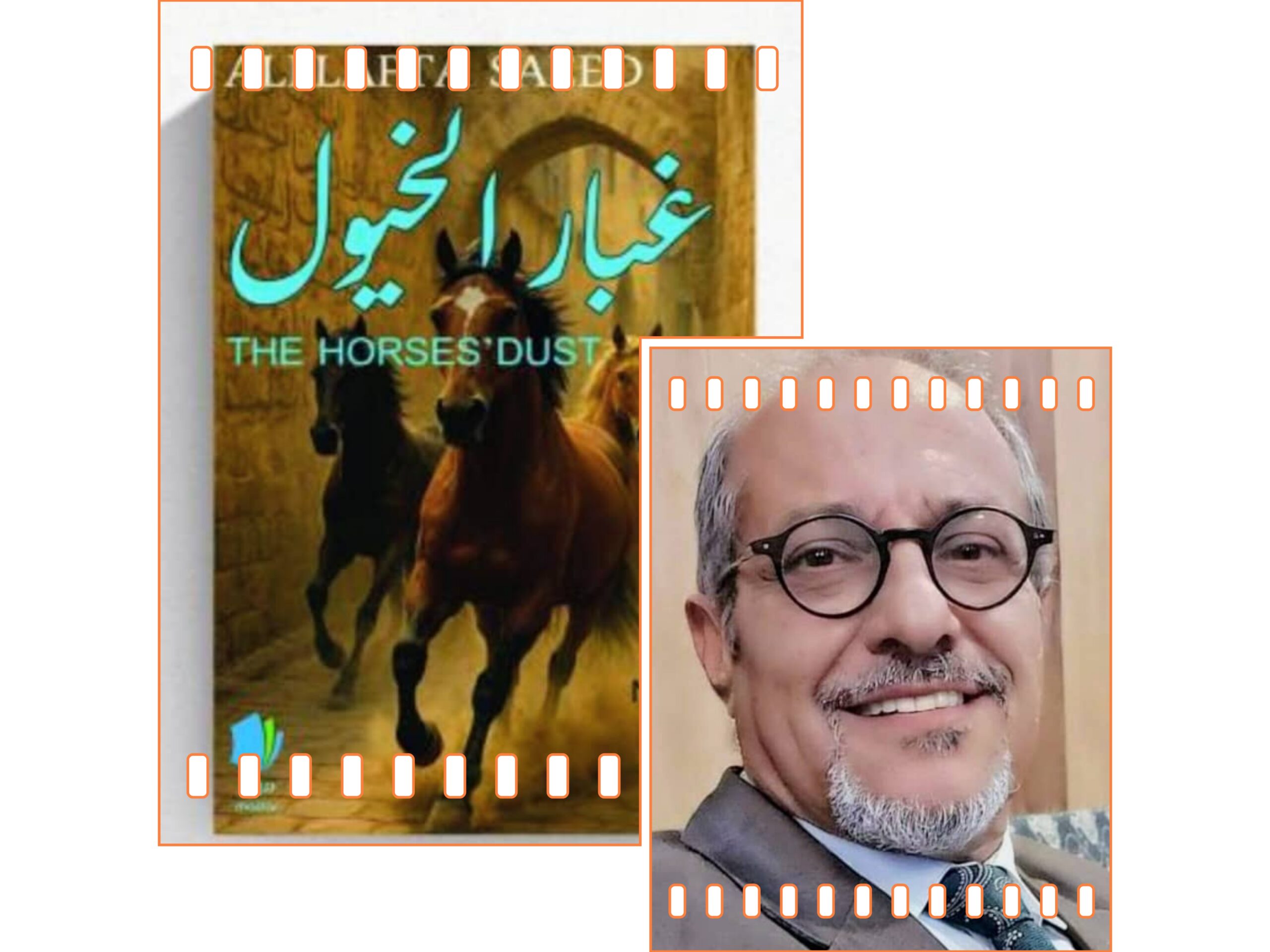

Dust of Horses) by Ali Lafta Saeed: Conflict as a Lived Consciousness, Not a Tale to Be Told)

Yemenat

Mohammed Al-Mekhlafi

(The conflict is exponentially spreading all over the place. On the forefront of casualties there lies intensive dust.)

With this sentence, the well-known Iraqi writer and novelist Ali Lafta Saeed opens his novel (Dust of Horses), published by Mayzar Publishing and Distribution in Sweden in its first edition in 2025. The novel spans approximately 169 pages.

From the very first line, the reader is not presented with a clear beginning. Instead, one is drawn directly into an ongoing and extended state that does not aim to explain events as much as it reveals their persistence.

Conflict here is not a fleeting incident that can be overcome. It is a mental condition that repeats itself and leaves its imprint long after its noise has faded.

What stands out most in the novel is the transformation of conflict into a component of daily consciousness, remaining present in every moment of life. The dust it leaves behind does not easily disperse. It clings to memory, seeps into language, and shapes the way the world is perceived.

The novel does not ask the reader what happened. Rather, it raises a deeper question. How is conflict lived when it shifts from a historical event into a daily state of awareness? How can narrative capture the continuation of violence that is not directly seen? In the end, nothing remains of violence except an absence that is nonetheless deeply felt.

Dust in this novel is not a secondary byproduct. It is what remains after every confrontation and continues to exist even after events themselves have settled. It stays present in thought, in narration, and in the human relationship with time and place.

Through this approach, the novel offers an experience that is not recounted from the outside but lived from within as a state of consciousness rather than a mere sequence of events.

While reading the opening pages, there is a growing sense that what lies ahead is not entirely new but something that keeps repeating and may still be repeating even now. This dust appears as the residue of all that has happened and continues to happen.

It is something that clings and resists erasure. The narrative moves between events and dates well known to the reader without pausing to explain or categorize them, as though the author assumes from the outset that this knowledge is already shared.

When these dates appear, they are not presented as a closed past but as forces that continue to shape how we think and how we view the country and what unfolds within it. History here is ongoing. It presses upon the present more than it explains it.

The narrative voice itself does not sound confident or decisive. It raises no slogans and does not attempt to persuade the reader to adopt a specific position. Instead, there is clear hesitation, persistent doubt, and a sense of exhaustion toward words that have been repeated too often.

Even when violence and bloodshed are addressed, they are conveyed in a subdued tone closer to confession than accusation. The narrator seems to articulate what everyone already knows, yet feels compelled to return to it because it remains inseparable from his daily life and thinking.

The relationship with the brother is not depicted as one of guidance but of searching. The brother offers no ready answers and does not present himself as a model to follow.

He chooses a different path, one rooted in contemplation and distance from noise. This path does not resolve the problem, but it leaves a lasting impression on the narrator and pushes him toward deeper reflection rather than comfort.

When the novel shifts to another place, it does not feel like a new beginning. Travel offers no salvation. It is simply a continuation of the same condition.

The details of airports and brief encounters pass quietly through a consciousness that observes more than it immerses itself. Even moments that are expected to be joyful remain suspended, suggesting from the outset that distance from place does not mean distance from unresolved questions.

The narrative voice is not that of a storyteller recounting events but of a consciousness living the moment without a safe distance. The narrator exists within the experience while simultaneously observing himself.

He advances, retreats, and attempts to contain what is happening, yet often falls silent when the burden becomes too heavy.

This narrative consciousness remains anxious but not broken. Its anxiety does not lead to shouting but to continuous reflection. Even moments of success are met with doubt and questioning. Is this real? Does it deserve such weight? Or is it fleeting like everything that came before?

Time in the novel is not linear but overlapping. The present is burdened by repeated invocations of the past. War songs, memories of occupation, Gilgamesh, Cain and Abel appear not merely as cultural references but as temporal layers living within the present moment.

Memory acts as an intrusive force, entering the narrator’s consciousness while he is on his way to a festival or sitting in a car, without his ability to control it.

Even joy remains inseparable from the shadow of memory. Every moment of elation carries a trace of war, and every beautiful song awakens an older one tied to loss. The novel suggests that living in the present, for those emerging from violent contexts, is not a given but a daily effort.

Place becomes a sensory and psychological experience rather than a geographical one. Tunisia is not described through fixed features but lived through the hotel, the festival, and the desert road.

The narrator does not ask what exists here but what happens to him here. Cities overlap, and Iraq suddenly resurfaces in a Tunisian street or a hotel room. Place becomes a mirror of collective memory.

The central tension of the novel lies between poetry as an individual means of salvation and reality as a collective pressure.

The narrator insists on poetry not as a luxury but as a necessity for survival and inner repair. Opposing this stands a reality burdened by authority, fanaticism, and ready-made discourse.

The novel does not promote poetry in a propagandistic way, but presents it as the only means of preventing collapse.

The characters appear more as mental states than as fully developed figures. Mossad flees commitment. The brother Abdulnasser is sealed within singular certainty. Najm confronts authority.

The wife represents simple safety. The general embodies the self’s conflict with itself. Each leaves an impression without the need for detailed development.

The language itself adopts an openness that allows narrative and poetry to interweave seamlessly. Poetic passages emerge precisely when prose can no longer bear the weight. The language permits itself to falter, to loosen deliberately, and to present thoughts that remain unresolved.

This openness reflects honestly the state of consciousness the novel seeks to portray.

The novel moves through segments resembling diary entries or adjacent fragments of awareness, without a traditional climax or final resolution. Its ending leaves the reader in a complex state of fullness, questioning, and incompleteness.

In the end, (Dust of Horses) does not aim to deliver truths but to record traces of passage. It captures the residue of cities, festivals, poetry, and an unsettled memory. It is a novel about a human being struggling to remain intact in a world that offers little support, finding in poetry a temporary refuge for survival.