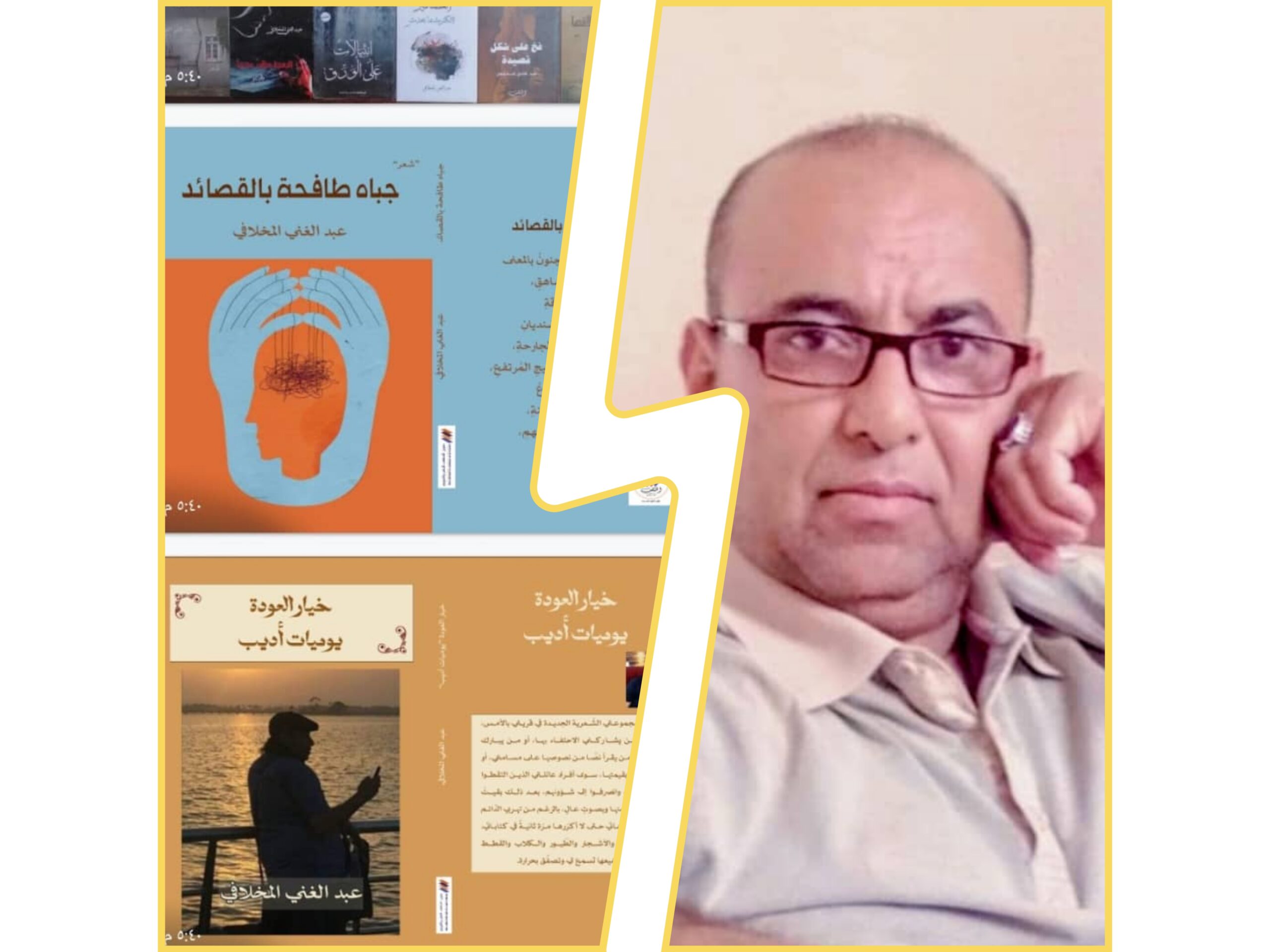

From Failure to Literary Fame: How Abdulghani Al-Mekhlafi Rose After Leaving School in Sixth Grade

Yemenat

Interview by: Mohammed Al-Mekhlafi

When I began speaking with the Yemeni poet Abdulghani Al-Mekhlafi, I immediately felt the richness of knowledge and culture flowing from his words. Despite his formal education ending in the sixth grade and society branding him a failure, he succeeded in shaping himself into a distinguished poet and writer. His childhood, full of imagination and a spirit of adventure, left a clear mark on his writings, which range from rhythmic poetry and prose poems to short stories and literary and intellectual essays. Each piece reflects his profound sensitivity to the world and embodies a way of thinking that blends imagination with wisdom, creating a literary experience that resonates with readers from the very first moment.

Childhood and Adventure

He described how his love for listening to stories and reading children’s tales sparked his initial interest in literature, noting his inclination toward adventure, contemplation, and weaving imaginations around mysterious things difficult to understand. He said:

“I enjoyed observing birds and animals, yet my grandfather would often punish me whenever he found me playing with dogs and cats, forbidding me from sitting at his table.”

He also painted a picture of nature’s beauty that inspired his young imagination, mentioning sunsets and the way the sun’s yellow glow kissed the clouds, turning these scenes in his mind into landscapes of forests and towering mountains—a world where imagined characters came alive. His childhood was never without a sense of adventure and cunning. He recalled:

“I would gather the children of relatives and suggest that we leave the village to live on an island in the open sea, free from the commands and punishments of our parents.”

He added: “When we tried to leave, nightfall caught us at the village exits, forcing us to retreat. I told them we would need a river stretching from the village to the sea so that we could travel safely on a boat we would make ourselves.”

Education and Memorizing the Quran

Despite this free spirit, his childhood was not without struggles. Reflecting on his school experience, he said:

“I rebelled against primary school and refused to continue in the following grades, earning ridicule and labels from those around me. I do not know the exact reason for my running away… perhaps because I was deprived of the embrace of my separated father and mother?”

Thus was formed a poetic spirit in which the fantasies of childhood melded with a keen observation of nature, where youthful freedom intertwined with experiences of loss—laying the foundation for his later poetry and worldview.

He explained that leaving school in the sixth grade and his insistence on not returning was considered a serious transgression at the time:

“How could I leave school at that age? What would I do if I were not with my peers at school?”

He described his sense of alienation and solitude:

“I remained an outlier, finding no companion in my rebellion. Reprimands from my parents struck me like bullets, the disdain of neighbors like lashes, and mothers would forbid their children from sitting with me, fearing they might be influenced.”

He added: “My friends labeled me a failure whenever I disagreed with them, and the people of my village repeatedly branded me the same way. All this deepened within me a sense of pain, insecurity, and the loss of my place among peers.”

He explained that his refuge from these pressures was always nature:

“During the day, I would escape the scornful eyes and reproaching tongues, angry and resentful, into the hills and valleys, chasing birds and animals, sometimes hiding behind my grandfather’s house on the high ridge, weaving in my imagination and dreams a path to leave the village.”

Describing his fear during the announcement of student exam results, he said: “I dreaded hearing: ‘Look at your outstanding classmates, you failure.’ Criticism was often meant to hurt, not out of care, but out of envy, malice, or ignorance.”

He concluded this phase of his life: “All this psychological harm left deeply painful marks. Had I not overcome it through later achievements, my reaction toward a society that lashes you constantly would have been aggressive. Anyone else subjected to this would likely suffer irreversible psychological wounds.”

He spoke of rejecting life with his stepmother after she tried to take him by force from his grandfather: “I escaped from the second-floor window of our house at sunset, wandering the streets after my grandfather had been threatened by my father not to receive me. How did my grandfather notice my escape, pursue me, and return me under his care, defying all threats?!”

He continued his story: Afterward, he lived with his grandfather, and his father no longer attempted to take him. He then devoted himself to memorizing the Quran under his grandfather’s guidance, who also taught children from the village and nearby villages. During this time, he discovered a deep passion for reading, falling in love with stories—especially the Green Library series for children, as well as folk epics such as Al-Zeer Salem, Antarah ibn Shaddad, Al-Maysa and Al-Miqdad, and One Thousand and One Nights. He successfully memorized fifteen parts of the Quran under his grandfather’s tutelage, which enriched his linguistic ability and nurtured his literary talent from a young age.

Regarding his love of reading from childhood, he said: “I immersed myself in children’s stories, and in my adolescence, I turned to poetry, memorizing works by Qais ibn Al-Mulawwah, Ibn Dharih, Urwah, Jamil, and Antarah. I left no romance novel unread, from the works of Al-Manfaluti to Naguib Mahfoudh, and the literature of Ihsan Abdelquddous. At the same time, I had a strong inclination toward romantic novels of that era.”

Literary Beginnings and Writing

Speaking of his early steps in writing, he said: “Whenever I finished reading a novel or story, I would immediately retell it to my friends, who were accustomed to listening to my stories. I even earned the nickname ‘the village storyteller.’ At the age of fifteen, I tried writing some reflections and short stories. Whenever I shared them with some teachers among my relatives, they would dismiss them—but paradoxically, their denial gave me a sense of confidence, as if I had written something beyond my age and experience.”

He spoke of his first published work as an unforgettable moment of joy:

“When I sent one of these attempts for publication and it was accepted without any intermediary, I felt an overwhelming happiness and proudly flaunted it among my peers. The surprise came when I was accused of theft. But I did not feel betrayed; on the contrary, it strengthened my belief in my talent and confirmed that what I wrote had real value.”

Reflecting on presenting one of his poems to his father, he said:

“I remember showing my father a poem published in Al-Jumhuriya newspaper. He was still regretful about my leaving school and did not believe it was my creation until he grasped its meaning—something no one else could express. He then proudly shared it with his friends.”

He added: “At that time, I published several poems, including one that gained attention for its profound summary of my emotional experience. The literary editor praised it, calling me promising. My confidence grew further when my father showed the poem to a prominent poet, who evaluated it positively. He asked if I had studied prosody, and I had never even heard of it or of Al-Khalil ibn Ahmed Al-Farahidi. He told me: ‘You write by instinct,’ and I nodded, not knowing what instinct meant.”

He described poetry as a purely emotional state of inspiration:

“A poem for me was a series of bursts. If inspiration stopped, I could not add a single word. My poems were metered, following the rhythms of classical Arabic poetry. As a friend of my father, a poet, said: instinct is what gives weight and connects meaning, but you must study prosody. You have a natural talent—work on refining it through reading and learning from others’ experiences.”

He also noted that his father was a significant cultural support:

“My father loved poetry and literature, was highly knowledgeable compared to others around him, and had memorized the Quran and taught it in his youth. I often turned to him to correct what I wrote. I remember when he said: ‘I no longer regret your leaving school; perhaps if you had studied, you wouldn’t write what you write today. This proves you have an innate gift.’ Seeing his joy brought me immense satisfaction.”

His emotional experiences became a driving force for writing:

“When my romantic life turned toward heartbreak, I wrote many poetic attempts, becoming like another Qais. My poems were published in newspapers and recited in gatherings. I never expected such follow-up and admiration—perhaps it was accepted for its deep emotion and sincerity.”

He added: “Often, people would point me out after seeing my photos in newspapers, giving me a sense of having become a star through my publications. I wrote to express my suppressed feelings, not for poetry’s sake.”

A Temporary Pause from Writing

Regarding his temporary halt from writing, he said: “When I stopped writing and publishing for a long time, people would ask me: ‘Why did you stop when you have such talent?’ I never considered what I wrote to be poetry, because I believed that poetry was written only by those with advanced degrees and experienced poets. How could I be a poet when I had completed no more than primary school?”

He also spoke of his passion for children’s TV shows and their influence on him: “I loved children’s series and had a dog named Kabi, inspired by them—rebellious and stubborn like me. I remember shows like Sinan, Flone, Oscar, Princess Yaqoot, Remi 0001, and Grendizer.”

He added: “Watching these series and listening to stories expanded my imagination and enriched my language. They helped build a world of concepts that later permeated my writings.”

Reading and Exploring World Literature

Touching on the works of contemporary poets and writers, he said:

“I studied the experiences of contemporary poets such as Mahmoud Darwish, Nizar Qabbani, and Amal Dunqul, along with the literature of Naguib Mahfoudh, Tawfiq Al-Hakim, Taha Hussein, Al-Aqqad, and Gibran Khalil Gibran. I also read novels such as Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo, The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky, and philosophical works like Discourse on Method by Descartes and Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Nietzsche. I was also influenced by Anis Mansour, Ghada Al-Samman, and the novels of Wassini Al-Aaraj and Malek Haddad, in addition to the masterpieces of Arabic literature, which broadened my horizons and deepened my literary awareness.”

Regarding his experience abroad, he said:”Without the opportunity to live abroad, I would not have reached this level. At home, one is limited to work, spending the day seeking a livelihood. It is difficult to access resources like buying books, owning a computer, or having home internet. As a self-reliant person, it is hard to continue creating in a country that does not provide these means.”

He added: “I lived in a private residence with internet and a laptop, alongside a library full of books, and a sense of stability that greatly helped me. Without traveling, I would not have had the chance to explore modern poetry and literature online or interact with fellow writers who recognized my ability to write prose poetry. Without this, I might have remained confined to traditional literary forms or stopped writing altogether.”

He explained how exile shaped his literary development:

“Spending twenty-two years abroad helped me develop my tools and mature my literary experience. During this period, I published six works and built a network of connections and reach through social media, extending my virtual presence across the globe. Each publication reflects part of my life and creative journey, making it difficult to prefer one over another.”

Despite all this, he spoke of the challenges of living in exile in recent years:

“I grew tired of exile, especially with new regulations making life there unbearably difficult. Expatriates find fewer opportunities, weighed down by requirements only large business owners can meet, while small project owners like us struggle, often relying on loans. Meanwhile, the homeland suffers a severe crisis, with a dire economy and scarce jobs. The war has exhausted everyone, emptied citizens’ pockets, and left employees unpaid. I endured a long time, but staying abroad became harder than returning. I decided to come back to spend the rest of my life at home, opening a small shop to meet my needs and those of my family—enough, without expecting more.”

Returning Home

He said: “Since I returned by evading restrictions, I faced multiple dangers that nearly cost me my life, were it not for God’s protection. Upon reaching my family, my joy was immense, a mix of astonishment and gratitude, between the fear that had lifted and the happiness I could barely comprehend in the moment.”

He described the reality after returning:

“In my homeland, especially in my community, I encountered malice in the form of envy, jealousy, and rejection, as if I were a stranger! Why? Because I had taken a different path? One would expect the opposite, as I represent not only myself but also my family, community, and country. Some people I considered closer than a brother were instead waiting for my fall. Jealousy and envy are disgraceful traits, and one must hide when sensing them.”

He noted the personal impact of this: “I was not angry, but I was hurt when it turned into outright hostility. I thought that by returning, I would make up for years away from family and friends and travel freely across my homeland. I did not expect an exile harsher than the one abroad; the previous exile was not this suffocating and monotonous.”

On the cultural scene at home, he said: “In reality, there is hardly any visible cultural activity, except for some individual or group initiatives outside official cultural institutions. Official activities are often controlled and limited to the parties in conflict, rather than arising from genuine cultural interest. Most creators today work individually and virtually, focusing their presence on social media spaces that have replaced absent official platforms.”

Literary Output

He concluded: “A week ago, I completed a new poetry collection titled The Tracks of Panting, my tenth attempt in prose poetry, and my thirteenth book overall. This collection joins two previous manuscripts awaiting publication. I attempt to explore the inner spaces of the weary human, capturing existential panting in a troubled reality, open to the possibilities of anxiety and fading.”

He added: “I hope literature and creators receive more attention in our homelands, and that the free word continues to express human experience and reality. Culture should play an active role in bridging gaps and easing isolation and neglect. In conclusion, I extend my sincere thanks and appreciation to everyone who seeks to highlight local and Arab creative experiences and support literature and culture—this reflects genuine awareness and care for the future of creativity.”

From “Beings of Dust”

Friends are coal, ashes in the eyes

The paths are dim, the dream a lamp extinguished

The place is seized

The leaves without sap

No tremor in existence

Emptiness upon emptiness

The sky is dark

No herald, no calm

The days are lean

The birds without throats.

The sun leans toward the den of sunset

The mountains wear the cloak of darkness

I curl upon myself

With tearful eyes

What of those who return in dire need,

Hands empty?

Of those who never attained,

Of him who licks a piece of meat with his eyes

At the butcher’s stall, feeling his hunger before the watermelon

And a kilo of oranges.

Of trees without birds

Of fields without ears of grain

Of houses without light, of roads without pedestrians

And of fathers bound in the chains of destitution